US Manufacturing Decline: Why It Happened and What It Means for Global Industry

When people talk about the US manufacturing decline, the steady reduction in industrial output, factory jobs, and domestic production capacity in the United States since the late 20th century. Also known as deindustrialization, it’s not just a story of factories closing—it’s about how global trade rules, automation, and policy choices reshaped who makes what, and where. Between 1998 and 2010, the U.S. lost over 5 million manufacturing jobs. That’s not just numbers—it’s entire towns losing their economic backbone. Places like Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh didn’t just see plants shut down—they saw generations of skilled workers forced into jobs that paid less, offered no benefits, or didn’t exist at all.

The supply chain disruption, the breakdown in reliable, local production networks that once kept American factories running. Also known as just-in-time logistics, it was meant to save money—but it made the system fragile. When the pandemic hit, the U.S. couldn’t make basic masks or medical supplies because the parts came from halfway across the world. Meanwhile, countries like China invested billions in building their own industrial ecosystems, while the U.S. focused on services and finance. The industrial policy, government strategies that determine how, where, and why manufacturing happens. Also known as economic planning, it’s what countries like Germany and Japan use to protect their factories. The U.S. didn’t have one—until recently. Now, the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS Act are trying to fix it, but rebuilding a lost industry takes decades, not years.

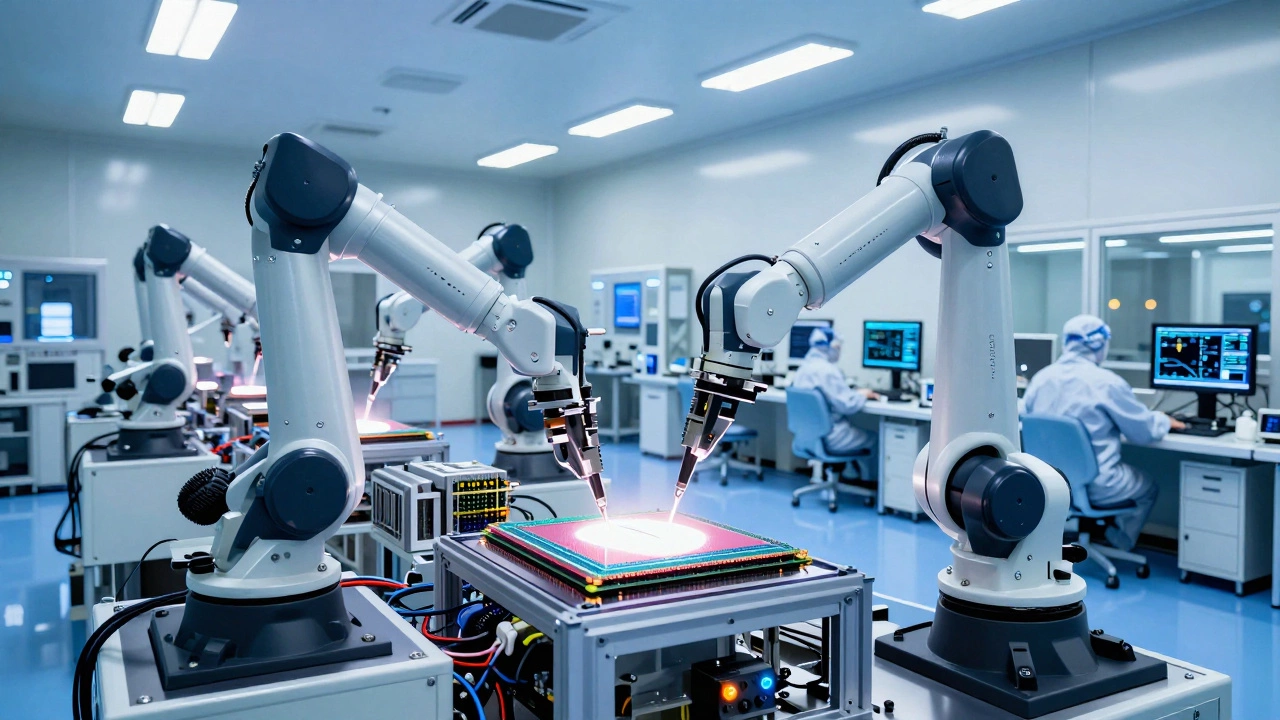

And then there’s automation. Machines didn’t cause the decline—they just sped it up. Factories that survived did so by using robots, not people. That’s why productivity went up while employment kept falling. You can’t blame workers for losing jobs to machines when those machines were bought with tax breaks and cheap loans. Meanwhile, countries with lower wages and fewer regulations pulled ahead in cost-sensitive industries like textiles, electronics, and furniture. India and Vietnam didn’t just take over—they built entire supply chains from scratch, while U.S. companies focused on branding, not making.

What’s left today isn’t gone—it’s changed. High-tech manufacturing still exists in the U.S., but it’s concentrated in aerospace, defense, and semiconductors. The everyday stuff—your phone charger, your sneakers, your kitchen utensils—those are made elsewhere. And that’s not because Americans don’t want to make things. It’s because the system stopped rewarding it. The US manufacturing decline wasn’t an accident. It was a choice. And now, the world is watching to see if the U.S. can make a different one.

Below, you’ll find real stories from countries that faced the same choices—and what happened when they did. From failed car brands in India to the rise of Chinese EVs in the U.S., these posts show how global manufacturing really works. Not in theory. Not in reports. In factories, supply chains, and the people who keep them running.

Is Manufacturing Down in the US? Real Data on Trends, Jobs, and Government Help

US manufacturing output is at record highs despite fewer workers. Government programs like the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act are driving a tech-driven revival in semiconductors, batteries, and clean energy production.

Read More